Six-pack muscle

Scarab is designed as a flexible modular platform intended for roles including agriculture and forestry, airport firefighting and adventure tourism

Six-pack muscle

EMotive’s 12 t Scarab 6×6 electric off-road truck is designed to appeal to a range of industries including agriculture, forestry, quarrying, mining, adventure tourism and airfield firefighting – all areas where large zero-emissions vehicles are becoming increasingly attractive.

Managing director Dan Regan reports excitement about the vehicle from the agricultural industry in particular. “People in agriculture feel like they have been forgotten; a lot of innovation in the UK is supported by the government, but only in recent months have we started to see agriculture-themed Innovate UK projects in the spotlight,” he says. “However, in terms of commercial interest, airport fire tenders lead the way, largely in the Middle East where there is a lot of work around zero-emissions, zero-carbon cities, which will have airports.”

EMotive is also talking with an adventure tourism company in Iceland, an environmentally sensitive country with plenty of geothermal energy. “The Icelandic government loves the income from tourism, but doesn’t love big diesel buses, and they have a very clean way of charging EVs,” Regan notes.

As an idea, the Scarab had its genesis in the mind of inventor and entrepreneur Bruce Palmer as far back as 1999 when, long before founding the company, he began work on a prototype six-wheeled all-terrain vehicle intended for agricultural use. Wood and cardboard mock-ups led to a more substantial proof-of-concept vehicle dubbed the Mk1, which made use of Land Rover components, including the V8 petrol engine and driveline parts.

Working with this machine, Palmer learned a lot about suspension geometry and stability, particularly the balance between off-road ability and stability at speed on the road, Regan explains.

“He then started de-constructing this machine to build Prototype B, whose agility he experimented with, investigating axle travel and power distribution between the wheels, which was all mechanical at that stage,” he says. “That phase lasted until 2001, when he was confident that he’d come up with something that was scalable.”

“He then realised that it would take 6 or 7 years to get it into production and that the future of such vehicles would obviously be electric. Looking at the market for electric components, he found that it wasn’t ready, so he parked the project and waited for suitable components to become available in volume at the right price.”

By 2016, Regan continues, there were many small passenger cars available from major manufacturers, indicating that the time was right to move forward. Palmer then dusted off the project, created a company and approached a contractor in Dorset, southern England, that was doing a lot of design work for the UK’s Ministry of Defence, asking them to come up with a chassis design. “By 2019, they had come up with a good, robust design that could be manufactured in volume,” Regan says.

At that point, Palmer decided he needed an in-house development capability, and brought in electrical and control systems engineer Regan as MD. Regan brings experience of writing control software for power station gas turbine generators at UK company Centrax, and of managing, engineering and funding hybrid and electric powertrain design at Ashwoods Automotive, not far from Centrax, where he was also involved in the development of the innovative commercial vehicle telematics platform Lightfoot.

(Author’s photo)

Once on board, Regan began building the team that includes operations manager Josh Roles, chief design engineer Steve Eldridge and head of systems engineering Simon Williams.

Regan emphasises that the contractor’s design provided them with a sound basis for development. “We have made some major tweaks and modifications in the past few years, but the bones of what they designed are all still there,” he says. “From day one, it was built around the electric architecture; there would have been no point in taking what was a combustion-engined chassis and trying to shoehorn in an electric drivetrain.

“All the reports from Bruce’s early testing were provided to the contractor. They were given a brief on what the electric powertrain needed to do in terms of performance, and they designed the mechanicals around that using our specification, results from prototype tests and their own experience to create the current architecture.”

Driveline architecture

Williams spent 18 years with UK specialist military vehicle developer Supacat, including a period in charge of the electrification of the Jackal platform and several overseas deployments with military forces as a civilian contractor, gaining hands-on operational support and maintenance experience with end-users.

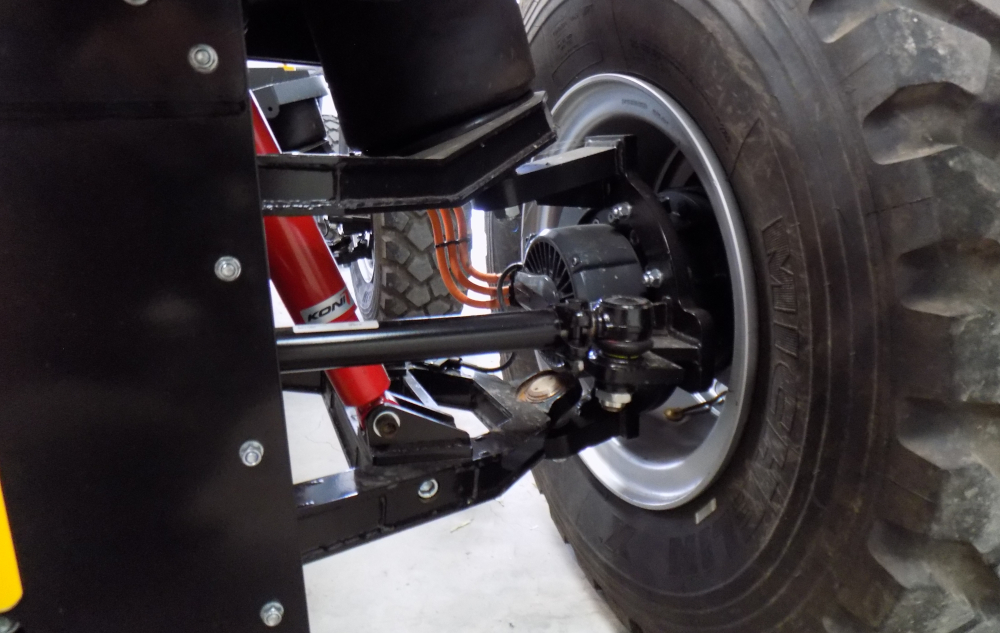

He explains that the driveline architecture is based on in-wheel propulsion, with, in the development prototype, a Dana electric motor coupled to a Lancereal reduction hub in each wheel. The modular design enables any number of axles up to six to be driven and/or steered.

Feeding that propulsion system in the Scarab prototype is a Webasto battery pack in an enclosure attached under the chassis rails between the centre and rear axles. An identical enclosure between the centre and front axles is empty at the moment, but it could house a second battery pack or a range extender.

Williams says EMotive is keeping its options open here, and could install an IC engine-based generator with several fuel options, including hydrogen when H2 combustion engines become available (from around 2024, he reckons) or a fuel cell stack. The company is now looking at how much power it can get from an IC-engined generator that will fit the available space, he notes.

“Combining a battery and range extender opens up applications such as underground mining,” Regan adds. “We are speaking to one company that uses explosives to extract minerals and now has to have three vehicles: one road vehicle to bring the explosives to the site, changing to an overground off-road vehicle, then changing again to one that can be run safely underground. With the Scarab, they could travel to the site on roads using the range extender, then switch to battery power to go underground.”

(Author’s photo)